Work in Progress

We Came With Our Own Riches:

How the Migrations of Black Folk Strengthened the Hamptons

Celebrated folklorist and author Patricia A. Turner, PhD, came of age in the Hamptons.

But not the luscious and lavish Hamptons inhabited by indolent damsels and degenerate playboys as long imagined by the purveyors of popular culture.

In the decade famous for Jazz Age excess, Turner’s parents arrived in search of fair and fertile grounds for their future. Born and raised in the Jim Crow South, Lloyd and Sallie Turner, and many other African-American families from their corner of southern Virginia, were seeking to escape the shackles of a race-based social system hard-wired to squash educational and economic mobility.

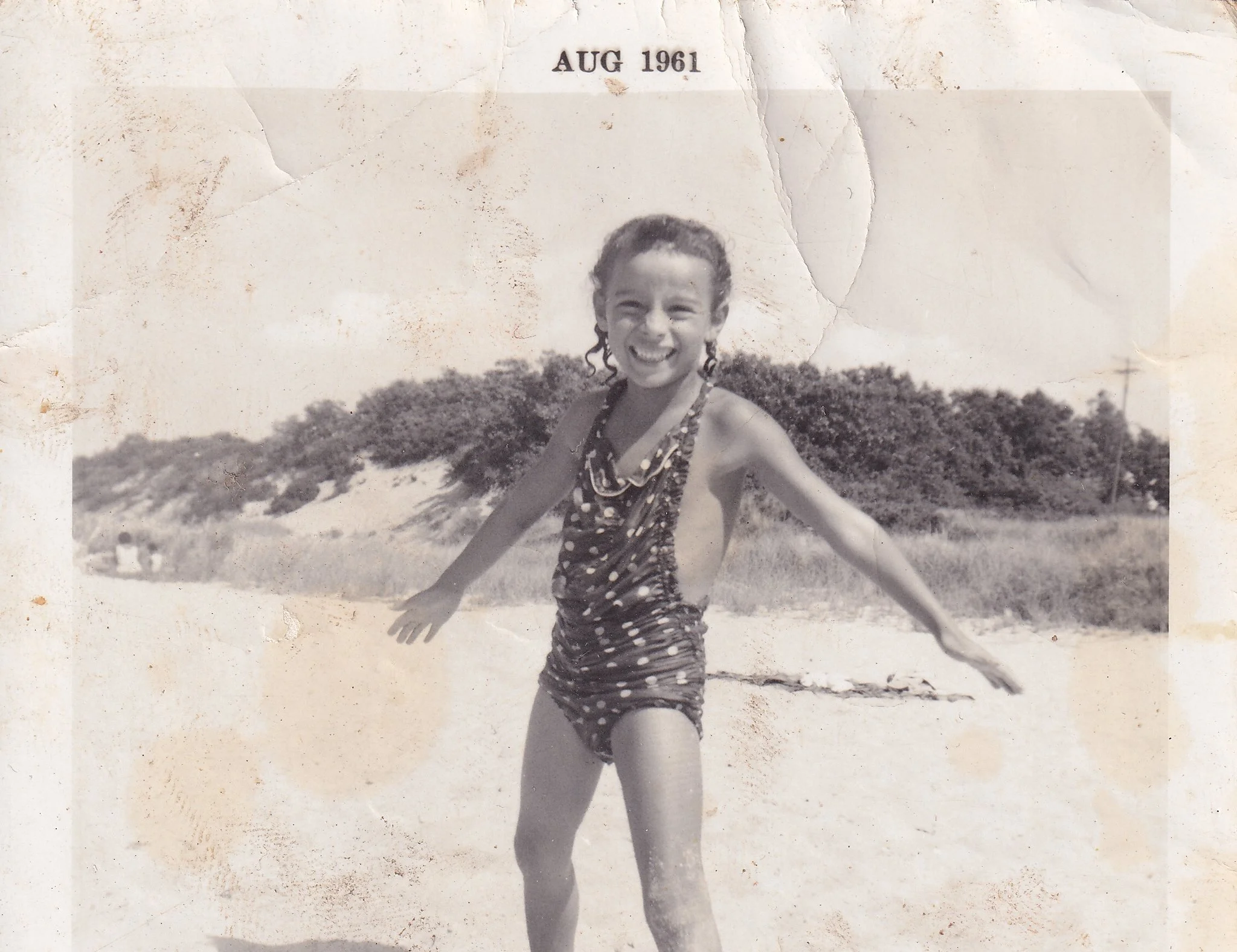

Patricia Turner, age 6, Sag Harbor Hills beach. Photo: Sykes-Turner Family Collection

Unlike similarly ambitious blacks who were enchanted by the bright lights and tall buildings of city life, the Turners—and many others who participated in this under-documented example of chain migration—preferred to work the land. They just didn’t want to be cheated out of their compensation and denied access to schools and stores.

With its thriving potato, duck, and fish farms, the Hamptons provided a rural working environment in which former sharecroppers could use the agricultural skills they had honed in the South and raise their families in a setting defined by fields and beaches rather than skyscrapers and factories.

Lula Mae Pettamay, potato harvesting season. Photo: Courtesy Judy Tomkins, The Other Hampton

In We Came With Own Riches: How The Migrations of Black Folk Strengthened The Hamptons, Turner documents the stories of the black population that has long been an essential component of the Hamptons’ economy.

Using archival sources containing compelling clues about her paternal and maternal ancestors’ challenging lives in Southampton County, Virginia, she reconstructs the harrowing circumstances that provoked so many early-twentieth-century blacks to take a chance on a new community several hundred miles from home.

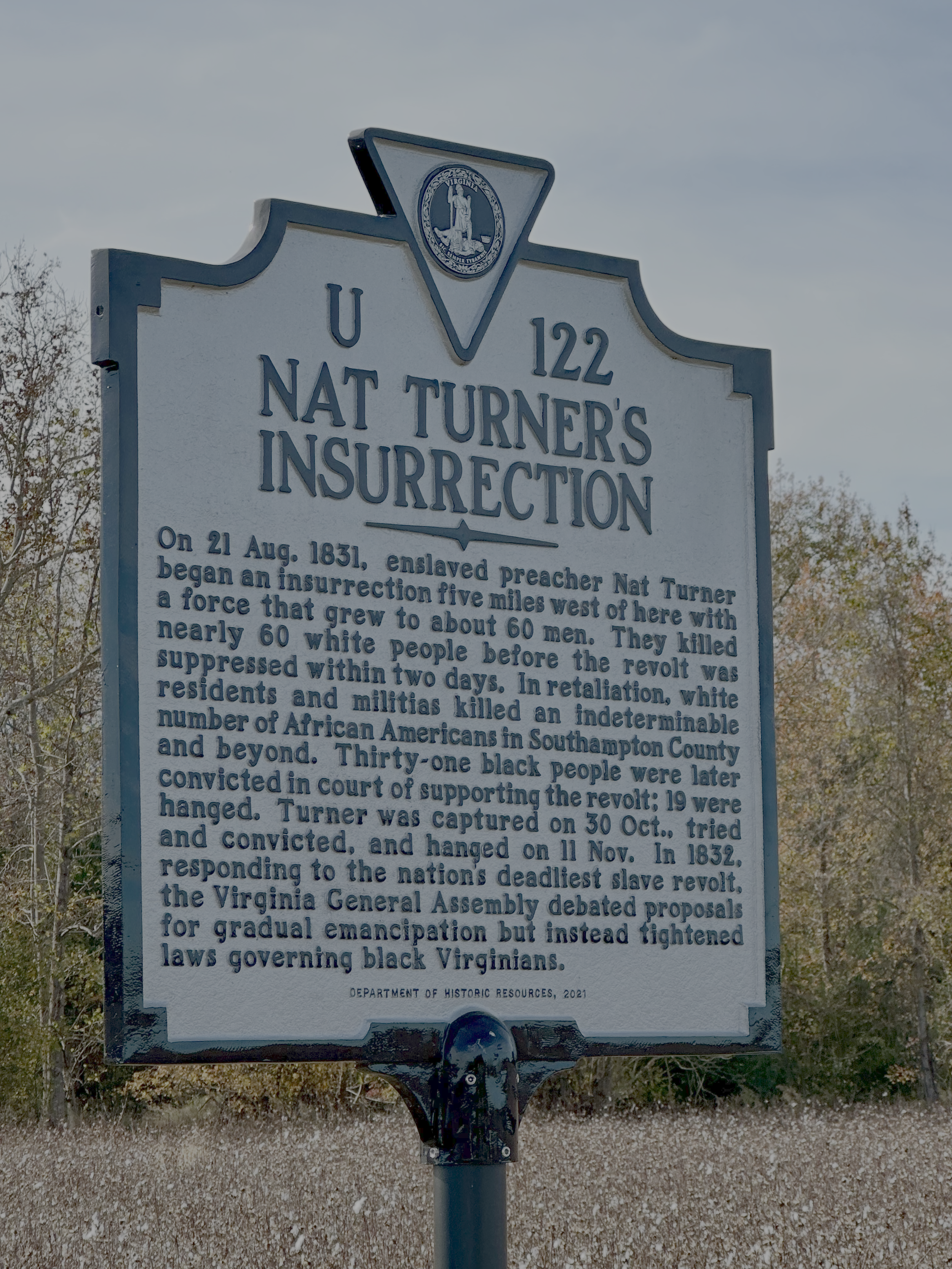

Well into the twentieth century, Southampton County, Virginia, site of the infamous 1831 rebellion of Nat Turner, exemplified the well-known obstacles and indignities fostered by an unapologetically white supremacist regime. But Turner’s hours in the archives and days on Virginia roads also revealed the spiritual and psychological assets nurtured by her ancestors and their neighbors that enabled them to make progress in the North.

“Nat Turner’s Insurrection” historical signage in Southampton County,Virginia. Photo: Patricia Turner

Just as the historical record pays little attention to the blacks who migrated to rural areas, it also glosses over the long existence of slavery in northern colonies.

From the earliest arrival of whites on Long Island in the 17th century, a blended population of enslaved peoples and Native American people were essential to the building of wealth in the whaling and maritime industries that empowered the eastern end of Long Island.

In telling the stories of indentured and enslaved individuals such as Pyrrhus Concer, Drusilla Crook, and many individuals documented only by their first names, Turner gives voice to blacks who carved out respectable lives for themselves and made meaningful contributions to their communities.

Born during the last decades of slavery in New York, Pyrrhus Concer (1814-1887) became a highly successful whaler and businessman. Photo: Southampton Public Library

From the Civil War to the Jazz Age

In the same decade that jazz age baron Henry du Pont built a fifty-room house on Meadow Lane in Southampton, trumpeter Demas Dean of Sag Harbor launched his career as an actual jazz pioneer, all of his training having taken place in Sag Harbor under the tutelage of his music maestro “Professor" James Van Houten, a veteran of a colored regiment in the Civil War.

A 19th century photograph of “Professor” James Van Houten (top left) and his Sag Harbor students. Photo: The John Jermain Memorial Library Sag Harbor Local History Archives Center.

With each passing decade of the twentieth century, African Americans expanded their reach throughout Southampton, East Hampton, Bridgehampton and the many surrounding villages that comprise the south fork of Long Island.

Although many members of the first generation of transplants were limited to farm labor in fields and barns or domestic work in the mansions of the wealthy, as their children made their way through the integrated school system, subsequent generations sought and succeeded at more challenging and lucrative occupations. Sons and daughters whose parents made do with repurposed outbuildings and outhouses built themselves single family homes complete with bathrooms and dining rooms.

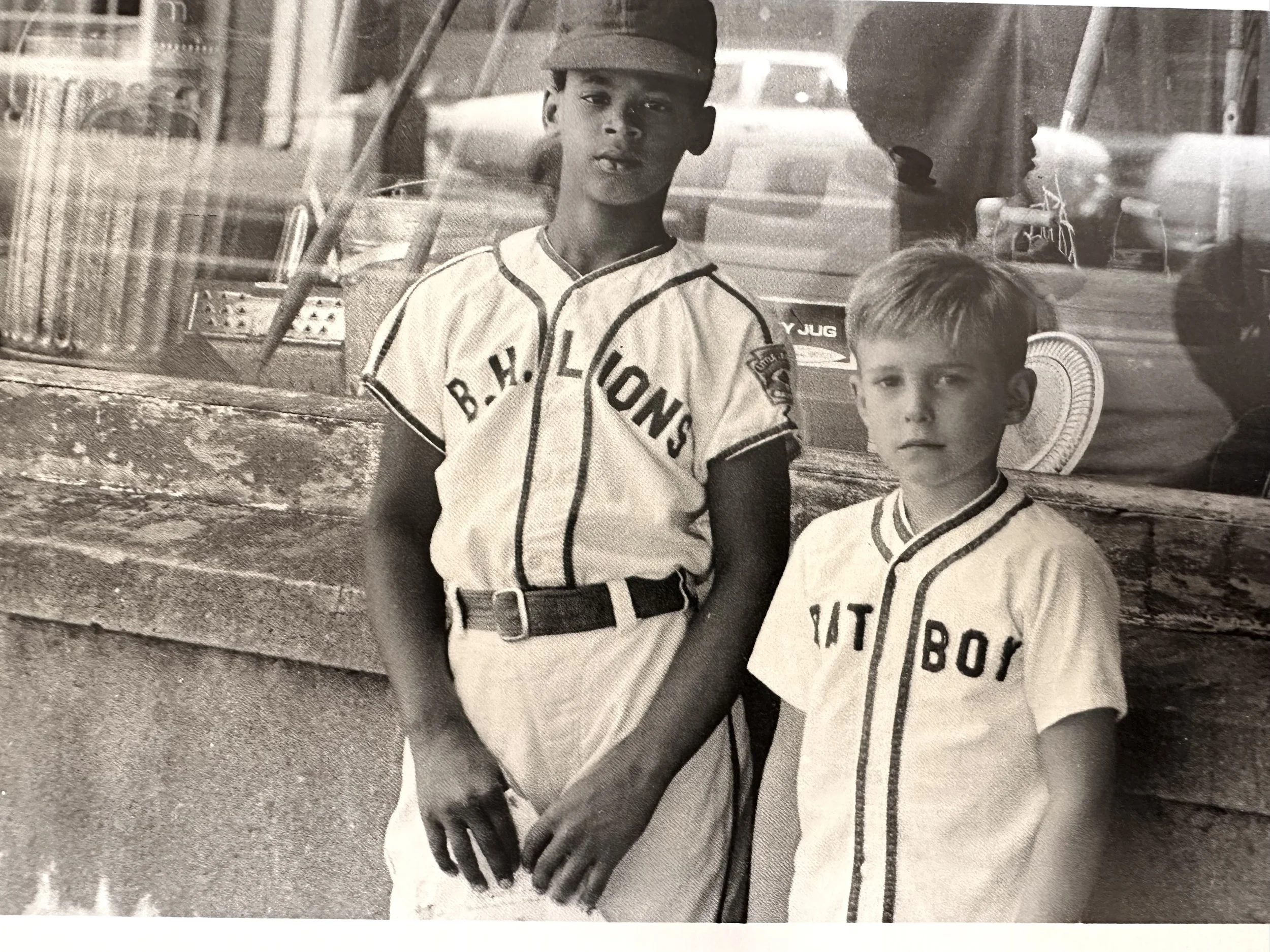

Amos Wyche and Billy DePetris. Photo: Judy Tomkins, The Other Hampton

Compared to the opulence of the mansions on East Hampton’s Lily Pond Lane and Bridgehampton’s Dune Road, these structures were strikingly modest. But they were honest homes where neighbors gathered for game nights in the winter and barbecues featuring delicacies every bit as tasty as any elsewhere were mainstays of the summer. To be sure, the Hamptons were not spared the sting of racism; even representatives of the Ku Klux Klan periodically infiltrated its institutions. But, unlike their southern home places they visited for church anniversaries and family milestone events, there were no Confederate statues or “whites only” signs.

The Anderson Family. Photo: Judy Tomkins, The Other Hampton

By boat, train, and car, accomplished entrepreneurs from the boroughs of New York discovered the Eastville section of Sag Harbor, thus beginning the establishment of one of the most enduring black recreational communities in the United States.

Turner tells the inspiring stories of these professional African Americans who set out in search of a less crowded setting where they could spend their weekends and summers away from the heat and chaos of the city.

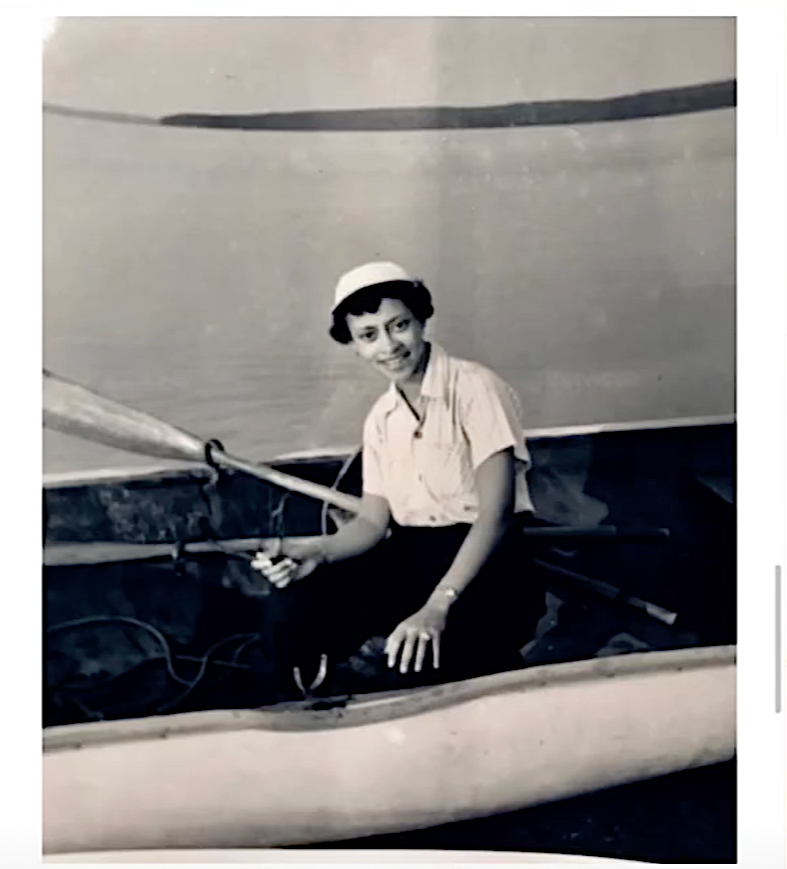

Gladys Barnes. Photo: © Courtesy the Barnes Family Archive

Heralded for their accomplishments in medicine, law, education, and other domains, pioneering black Sag Harborites had much to offer. The eminent physician H. Binga Dismond established medical offices both in Bridgehampton and Sag Harbor. Mary Kathleen “Kathy” Tucker, educator, served as executive director of the Bridgehampton Childcare Center.

Arthur H. Barnes on the steps of the original Dismond summer home in Sag Harbor. Photo: © Courtesy the Barnes Family Archive

After a career of exploring others’ stories, Turner’s own remarkable family constitutes the lodestar for We Came With Our Own Riches.

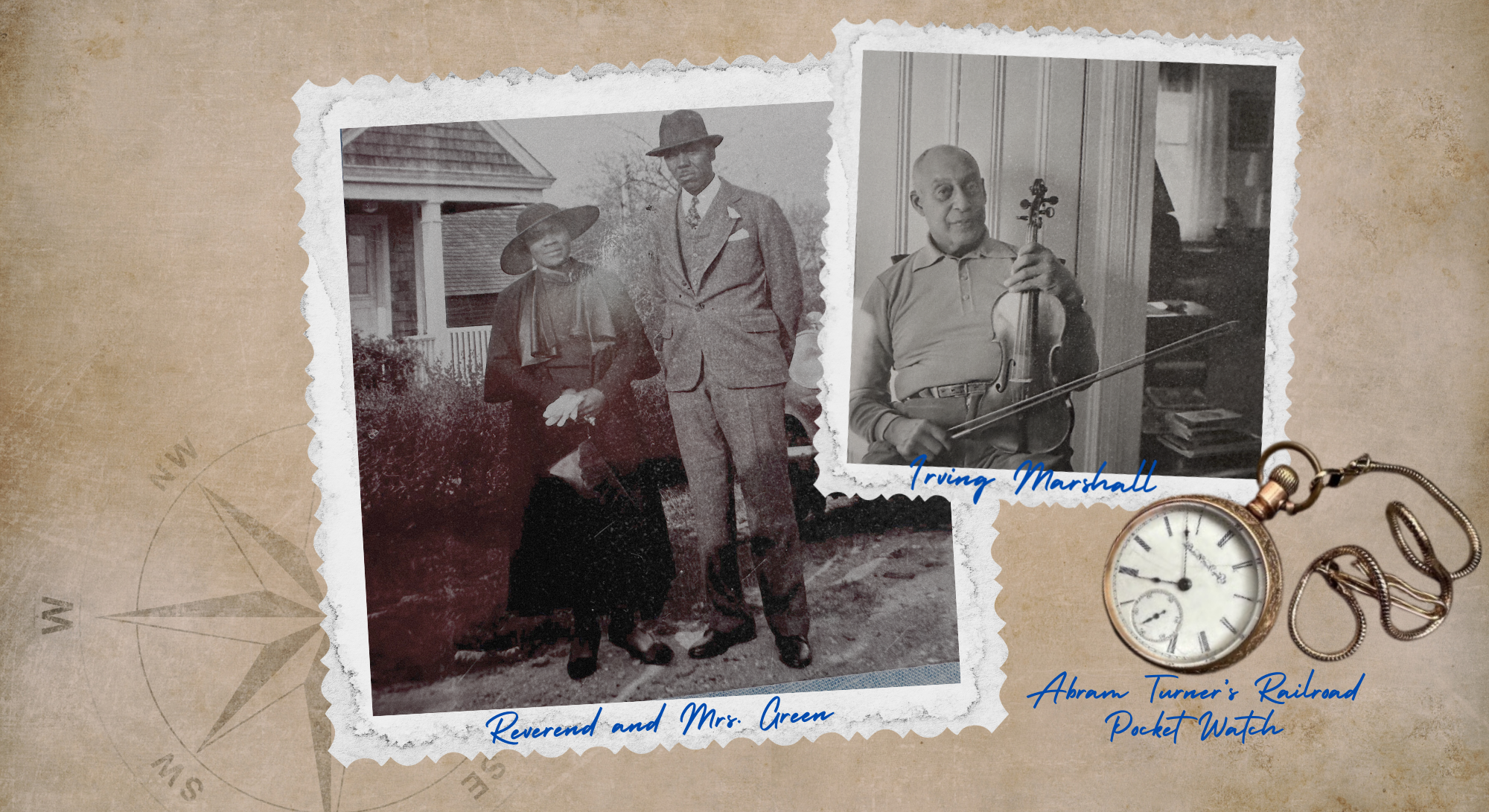

She begins by reconstructing the life of her paternal great grandfather, Abram Turner, born in 1846 in Drewryville, Virginia. Entering adulthood at the end of the Civil War, he was in the first cohort of black voters in Virginia. He legally married his beloved wife, moved from share-cropping to land ownership and secured a coveted position on the railroad in his senior years.

Gravestone reading ABRAM TURNER DIED 1919 AGE 72. Photo: Patricia Turner

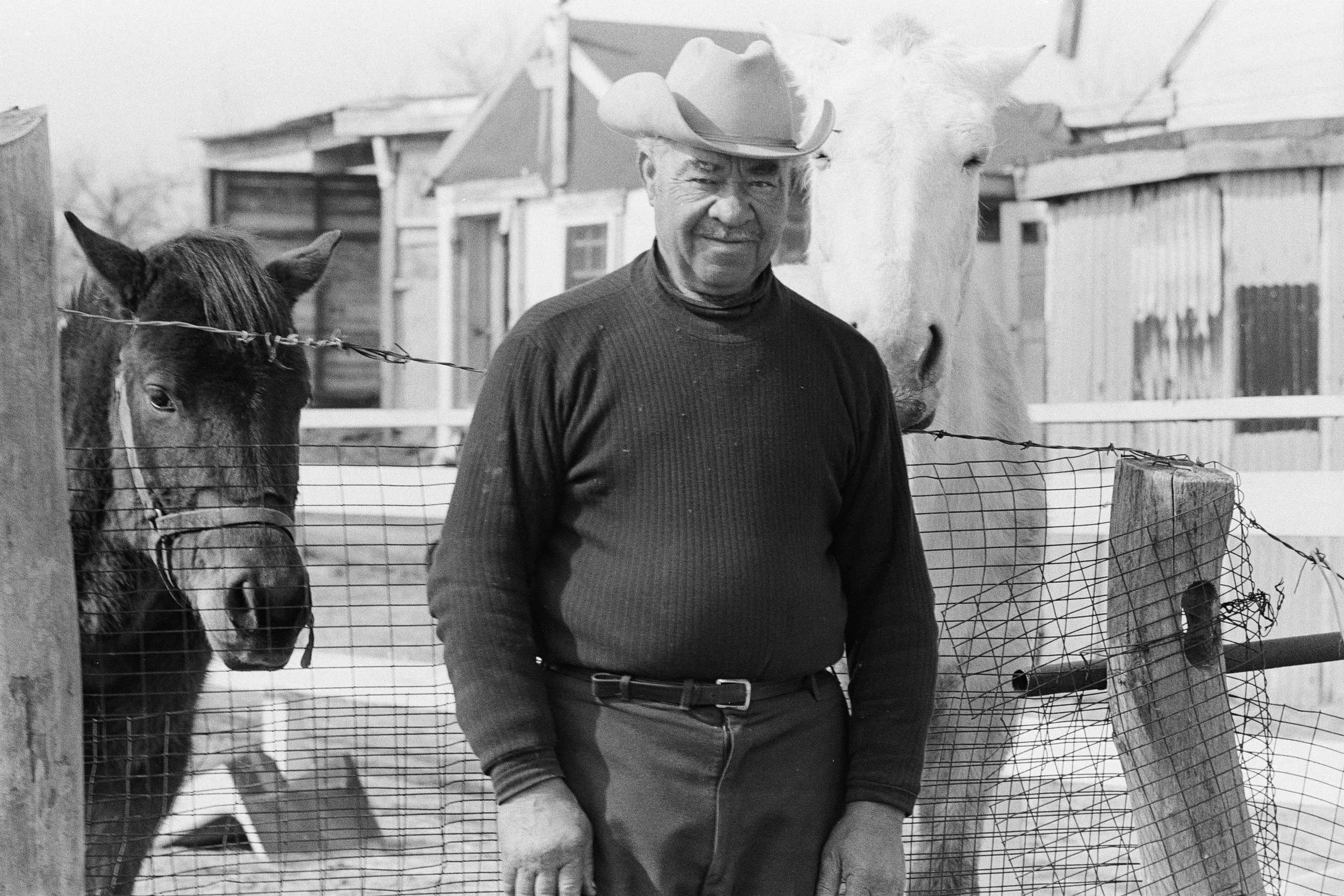

She ends with the story of Abram’s grandson, her father, Lloyd Turner and his much revered Old Hickory Farm which, for several decades, was a treasured local resource where children learned to ride horses and adults came to buy fresh eggs and vegetables right out of the garden. Following his death in the early 1990s, local environmentalists inaugurated and still maintain efforts to preserve the ecologically important trails he had introduced generations of horse-back riders to.

Lloyd Turner, horseman and entrepreneur. Photo: Judy Tomkins

We Came With Our Own Riches: How The Migrations of Black Folk Strengthened The Hamptons introduces the reader to people traditionally overlooked in the literature and history of the Hamptons.

Told with Turner’s signature warmth, humor, and rigorous research, her insider’s knowledge of, and fondness for, the Hamptons’ richly varied African American enclaves bring this neglected history and ethnography to life.

100th Anniversary Celebration of the First Baptist Church of Bridgehampton. Photo: Patricia Turner